The late US election inspired me, mixed with several of my customers suffering from their providers’ failure, and led me to write this post to remind about the reality, and not someone’s reality. When dealing with a provider, or selecting a one, you may thing about the consequences and his failure on your business: often, you’ll prefer a big player, as he might be too big to fall. Even if falling and failing are just a character away, they are far more different.

lem.mings (‘lem-ingz): adorable yet incredible stupid furry creatures. Without your help, they have no chance of survival.

Internet is dead! Nope, just Facebook

No need to go back to the beginning of Zuck’s company history: an ultra-fast search on your favorite search engine will lead you to a major crash beginning of 2020.

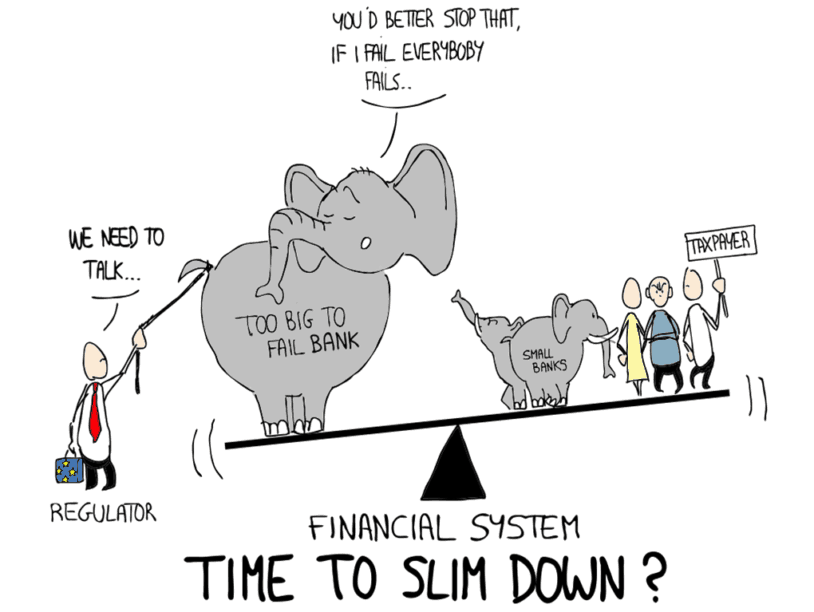

We often confuse failing our company’s box with failing our customers. That’s why I prefer the term “falling” in the first case. With this little vocabulary point, we can dig a little more into what we call the “To big to failfall”. This has been a recurring topic since the subprime crisis of 2008. The fact that banks can fall, disappear, what about the major players in each field.

Too-big-to-fail banks not only threaten our financial system – they also distort competition © Frédéric Hache / Finance Watch

The fall of “too big” would theoretically cause the whole system to fall. Although this is not without disastrous consequences, no system disappeared with the fall of the American banks. No system disappeared with the massive fall of the car manufacturers. Massive bankruptcies, unemployment, people on the street yes. But the system did not. So those “too big” can fall.

Well, that’s not really the subject of this post, but you’ve understood: we suppose that a big actor can’t disappear because we’ll do everything we can to hold him, because after all, if he were to disappear, we suppose the consequences would be far too disastrous. So let’s move on.

No one has ever been fired for opting for IBM

Choosing “too big” is reassuring. It is known, it has thousands of employees, it weighs hundreds of millions of dollars, … It cannot failfall. Nope, but it can fail.

The first source of error is and has always been human. This is the primary reason for relying on a principle such as HAZOP (HAZard and OPerability studies). The principle of HAZOP is the decomposition of the system to be analyzed into several subsets, called “nodes” so that the risk analysis can be shared between individuals or multidisciplinary teams. Assume that something will fail, and then you can prevent the risk. In fact, in IT, we often use the expression:

If everything went well, then you’ve forgotten something.

Not for nothing.

In 2017, AWS suffered a huge incident on its massive storage (AWS S3). This incident was the direct consequence of human error, to debug another situation. As a result, all companies relying on AWS’ S3 service in this region have been impacted by the service outage, but worse, some have lost data, with no hope of ever finding it again. How many customers have gone out of business due to a failure at AWS?

Very often, the first reaction of a customer of these “too big”, on this type of incident, is that given the massive failure, and the number of companies impacted, your own users, the end-users, will have other things to deal with.

This is true, but within a certain limit. On the other hand, it also shows that you have not calculated the risks, and assume that this risk would be borne unilaterally by this “too big”.

You said to say Hardy!

Very often, in order to respond to these human errors, we decide that the best way is the constraint, the limitation, the process. Do what you are told and strictly what you are told. This is how your “too big”, under cover of a Quality certification for example, will set up various levels of support, each with its own forms, processes, …

Here, we can echo one of my customers, who ordered from the largest French hosting provider (Hello there, OVH), servers, proudly announced available in 120s, without specifying the quantity. Well yes, marketing doesn’t have the same concern for quality process and transparency as technology: after all, it’s not a service ;)

Anyway, servers ordered, but only partially delivered two weeks later. Impossible to have a status because the delivery process is jammed. But the fun doesn’t stop there. In order not to be caught off guard, this customer decides to start installing the servers already delivered, using the tools of this provider. Except, that these tools are bug’d. A support ticket is opened, without reaction. The customer’s teams continue to work on it all the weekend, hoping to get the whole thing up and running, and at times, receive charming mails from the provider, as:

- you have set such a value to 0: except that the provider’s installation tool forbids such a value … which is only the result of a bug

- stop loop crashing: except that it crashes in a loop, because installing it crashes in a loop.

Solution proposed by the founder of OVH? Replace the famous servers with its Object Storage service. The same service, which has been in error for a week, with no solution, and where some customers are complaining about a loss of revenue of several thousand euros over the same period.

Better off Ted

And meanwhile, the mail open to the support, with all the details, is not read by the speakers. Why is this? It’s out of process! The emails are processed by the level 1 support, which doesn’t work on weekends, while the technicians on site only intervene on alarms. The link between the two in normal times? Level 2 support which can only be triggered by level 1. The famous level 1 unavailable. The process is therefore, once again, at fault.

Here it is possible to distinguish several failures:

- managerial, where the founder ignores the state of his department (voluntarily or not) and gives you inadequate recommendations

- supply chain, where a server is missing, with no possible information, and no possible billing for the supplier.

- support, where segmentation of teams prevents information from circulating correctly, preventing a technical solution from being implemented

Me, myself, and the Apocalypse

Such failures often go unnoticed by the mass of customers of these providers. However, if you take the time to search, you will always find customers. This becomes all the more true when these customers reach critical size.

So yes, one provider can be better than another (in fact, any truly professional provider is better than a low-cost provider). However, no one is infallible, and no one is too big in the face of fails.

If the service to be delivered to you is critical, then the skill levels of that provider are critical. But it is also your responsibility to have a plan-B outside of your provider. Processes (and certifications) will only serve you in court to ascertain whether the obligations of means and results have been met. Period.

How about you? Do you prefer “too big”?